07 Jul 2023 The Charming Folly at the bottom of Anlaby’s Garden

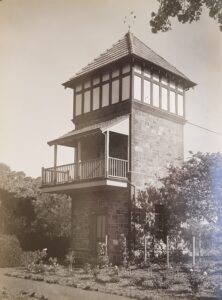

At the very bottom of the garden, on the south side of the Anlaby homestead, sits an enormous square tower. It soars above the canopy of elms and pears, proudly displaying its robust stone and brick walls and attractive terracotta tile roof. Why was this extravagant tower ever built?

Between 1890 and 1914, when Henry Dutton owned Anlaby, he completely transformed the heart of the estate. He augmented the size and grandeur of the house, expanded the gardens to 10 acres, and constructed dozens of buildings – from stables to conservatories – leaving behind an impressive built legacy. One such Henry-era building is the Tower, built in 1912.

During Henry’s time at Anlaby, any work undertaken to alter or add to the estate was meticulously recorded in wage books and cash books. Wage books, for example, are fantastic at identifying who worked at Anlaby, when, and how much they earned. In many cases, it even lists the type of work done: splitting fence posts, catching rabbits, laying pipes, cooking for shearers, and more. Unfortunately, wage books and cash books from around 1912 have not survived, making it difficult to pinpoint exactly when the tower was built.

Two newspaper articles unlock the key to the tower’s genesis. The first, published in the Kapunda Herald on 1 November 1912, details the search for underground water around the estate. A bore was sunk on the top of Mount Waterloo, located two kilometres north of the homestead, while a well was dug in the garden, “close to where the new water tower has been erected.” A second newspaper article, published in the Daily Herald on 19 November 1912, also mentions a well has been dug “adjacent to the water tower.” These are the first mentions of the tower in print.

Both newspaper articles explain that the search for water was so desperate because the gardens suffered through want of water in autumn 1912, and even sheep feed was diminishing. An article from 6 November 1912 published in The Register adds that the surface water supply – presumably meaning dams – was utterly exhausted. Underground water was discovered by Mr W. Kinter of Eudunda, who used divining rods to divine plentiful water supplies. Following Kinter’s visit to Anlaby on 9 September 1912, Henry referred to him as ‘The Divining Rod Man” in his diary. Over several visits to Anlaby in late 1912, he identified nine locations where he believed water would be found – including the Tower Well, established by November that year.

A water analysis 1912 undertaken by the South Australian School of Mines and Industries reveals the water quality in the Tower Well. The analysis tested the water for Sodium, Magnesium, and Calcium and advised the water could “be used for general irrigation without ill effects.” It added: “It would be advisable to apply the water in large quantities at a time….” This was good news for Henry and his head gardener, Thomas Leslie, for it provided the garden with a buffer against future droughts.

To give some context to the water shortage, from January to May 1912, Anlaby suffered from a serious lack of rainfall. In January, only 2.6mm fell when the average was 20.1mm. In February, only 7.1mm fell, though the average was 20.6mm. In March, 14.3mm fell, which was short of the average of 23.6mm. In April, 17.7mm fell – an increase, certainly – though still below the average of 37.5mm. The worst came in May 1912, when only 6.1mm fell: a long way short of the average of 53.5mm. The severe lack of rainfall between January and May 1912 – coming to only 30.7% of the expected average rainfall – wreaked havoc on the gardens and countryside at Anlaby. The dry spell, however, was more protracted than this. 1911 was a below-average year: 375mm fell, as opposed to the average of 500mm, with rainfall totals taking a steep dive toward year’s end. A report on weather and crops in the Adelaide-based paper, Chronicle, published on 1 June 1912, described the ground around Anlaby as being “devoid of herbage, and the colour is an even greyish black.” It went on: “Sheep farmers are having a very bad time. The lambing is at hand, but many lambs are dying for want of feed…a good rain would revolutionise the appearance of the country.”

Rainfall records and accounts from the time make it clear why the tower was built, though after a reliable water source had been found next to the tower, how did it help water to the gardens? A water pump was installed in the shed built around the well to pump water up to the top of the tower, where four large water tanks, six feet deep, had been installed. From there, the water would be gravity-fed downwards into the garden. Much of the original machinery is still in place, though the tank is hidden behind structural beams and the tiled roof.

Though the tower was built primarily to bring water to the gardens, it was used by family, friends, and visitors in a number of different ways.

The first mention of the tower in Henry Dutton’s diary comes from 20th October 1912. He described the pleasant weather, recorded his attendance at church at 11am, then ended his entry with, “We all had tea in the Tower.” Whether this means afternoon tea or an evening meal is not clear, but it does show the tower was a place to gather, eat and enjoy. Ten days later, on 30 October – the same day a Garden Fete was held at Anlaby to raise funds for the St. Matthew’s Church Parish Hall at Hamilton – he describes having tea in the Tower with his daughter-in-law, Emily; his grandchildren, Richard and John; the Manager, Claude; and others. More mentions were made over the next few months.

Though no direct reference has yet been found, it is likely that onlookers stood on the balcony to watch tennis being played on the grass court below. Refreshments, too, may have been served to onlookers (not unlikely given that tea could be served there). In November 1917, the committee of the Kapunda Floral Society visited Anlaby to view the extensive gardens there. They marvelled at the famed pelargoniums, carnations, fuschias, azalias, and clematis flowers before ascending the stairs to the balcony of the water tower. One report said the view “gave the visitors a better idea of the extent and beauty of the place than can be gained from the ground level,” going on to remark that Emily Dutton’s skill at floriculture, and Harry’s passion for arboriculture, was distinctly visible from the higher position. Visitors to garden fetes, and even groups travelling to marvel at the gardens, would often ascend the stairs to stare in awe at the 10-acre garden.

During the 1920s and 1930s, Geoffrey Dutton remembers his mother, Emily, practicing piano and violin on the ground floor of the tower. An American-made piano was installed there for her to play! Geoffrey, too, used the tower as a place to write. In his autobiography – in which he calls the tower ‘Grandfather’s Folly’ – he commented that even on a hot summer’s day, it was always cool inside thanks to the water tanks on the top storey. As a young boy, Geoffrey had been introduced to watercolour painting, so he spent many hours capturing the view of the tower from the drawing room at the front of the house.

The tower at Anlaby has, more recently, taken on the name ‘Folly’ – though the origin of the name is not clear. It may have been first coined by Geoffrey and slipped into common knowledge as the building’s origins were forgotten. Traditionally, a folly structure is an extravagant building found in large gardens or parks, often with no practical purpose. Some were built deliberately to look like ruins – at great cost – to create an air of ancient aesthetic beauty. The term ‘folly’ could also be seen, in this case, as an example of the wildly extravagant vision Henry Dutton realised at Anlaby between his arrival in 1890 and his death in 1914. Either way, it is a commanding structure offering perspective and inspiration.