15 Mar 2024 A major discovery: Overturning Anlaby’s story

Anlaby benefits from an enormous wealth of documents detailing the turbulent life of the property; at the State Library of South Australia, there are 42 metres of shelves with records relating to Anlaby, with more material located at the National Library of Australia and in the private Dutton family collection. The challenge is finding the proverbial needle in a haystack. Such a trove of material inevitably turns up new information that completely redefines our understanding of Anlaby. A major discovery has been made regarding the construction of the main homestead, which was the home of the Dutton family for four generations and originally constructed as a manager’s residence. What new information has come to light?

For decades, the true nature of the construction of the main homestead at Anlaby has been shrouded in mystery. Historical sources have differed widely as to when it was built. Some have vaguely hinted at extensions and modifications to the first house built for the second manager, Alexander Buchanan, while others have broadly suggested the 1850s or 1860s as the most likely date of construction.

Until now, it was understood that the main residence was constructed in 1861, owing to an architectural plan supposedly dated to that year.

The truth, as it turns out, it far more intriguing and exciting!

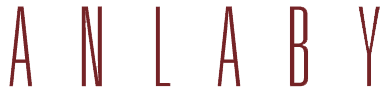

This story of discovery starts with an architectural plan of Anlaby that exists at the National Library of Australia. It is titled ‘Plans for the Residence of Alexr. Buchanan Anlaby,’ and details the eastern and principal elevations of the house. It is a photographic copy of the original plan, captured by the architectural historian, Wes Stacey,around 1970. In Stacey’s photograph, the fine handwriting at the bottom right is obscured; it reads ‘English and Brown Adelaide ……’ before petering out.

Despite petering out, one detail – the identity of the architectural firm – can be determined. The partnership, English & Brown, was established around 1850 by Thomas English and Henry Brown. English was a trained architect, while Brown was a builder contractor by trade, so the two went hand in hand. They started trading on Carrington Street, Adelaide, and acquired a sandstone quarry at Tea Tree Gully around 1852. Operating during a boom time in South Australia’s early years, the firm received several high-profile contracts: Parliament House (1854), extensions to Government House (1855/6), Scots Church (1858), the South Australian Institute (1860), and parts of Adelaide Gaol (1862). The partnership lasted until 1865, owing to the fact that Thomas English had become a Member of the Legislative Council and the Minister for Works, which barred him from simultaneously serving as an architect. Henry Brown formed a new partnership and continued working for decades thereafter. This small detail from Stacey’s photograph confirms that Anlaby was designed by English & Brown between 1850 and 1865.

The next step in the story occurred in December 2022, when several copies of architectural plans were received at Anlaby, copies of which were hung in the onsite accommodation, like the Gardener’s Cottage or Coachman’s Cottage. The scans were taken from original plans privately held by the Dutton family. One of the scans looked identical to the one held at the National Library, but the quality was far better. It also included a very important detail: the handwriting at the bottom right was unobscured. It read, ‘English & Brown, Adelaide, April 1857.’ Excitingly, a date had been identified, but it raised a multitude of questions. Whilst it’s not unusual for architectural plans to be drawn up in advance, could the house be older than believed? How long did it really take to construct the house? What additional evidence could be found to shed light on the construction of the house?

In an attempt to resolve the mystery surrounding the homestead’s construction, it was necessary to travel to the State Library of South Australia in search of answers. The first step was to start leafing through hefty, leather-bound ledger books from the year 1857. The ledger books record all income and expenses – from worker’s wages and the sale of wool to the purchase of rations and the auctioning of livestock. Thankfully, most of the ledgers contain an alphabetical index – sometimes located at the front, sometimes neatly pasted to the back page – but it was hardly needed here: while looking for an index at the front of the ledger, the fourth page opened up, and at the top, in large, cursive handwriting, was written ‘House Account.’ Eureka!

Here, in remarkable detail, was the beginning of an itemised account, starting in February 1857, that recorded all expenses incurred to construct the main house. On 20 February, the first item details the payment of £120 for 8000 slates, at a rate of £15 per 1000. A week later, John Craig, a settler along the River Light, received payment for carting slates to Anlaby, at a rate of £2 per ton, and over the next month he carted around eleven tons of slates to Anlaby. Craig was helped by John Mungo, a settler at Sower Flats; William Coombes, a resident from the River Light, John Williams of Allen’s Creek; and William Wrigley, an employee at Anlaby. Over the following months they carted tons of timber and slates, as well as white lead, cedar wood, carpenter’s tools, door hinges, and locks.

Thomas English and Henry Brown of English & Brown were the ideal choice for Anlaby: they not only designed the house but also provided building material. In June they provided timber to the tune of £271 9s 5d, which equates to $48,000 in 2023. They continued to supply timber throughout construction.

Scaffolding was being erected by July 1857, thanks to the work of James Rusher, who was already employed at Anlaby as a fencer and hut builder. Quarrying was also taking place: Nicholas Pascoe, Samuel Potter, and Thomas Hodges were all paid for weeks of hard labour in July. It is very likely they used a local quarry to source the necessary stone, for if it were quarried at the English & Brown quarry at Tea Tree Gully, the carting charges would be considerably higher.

The following month, Richard Dooley, William Ireson, Robert Anderson, Henry Jones, and Thomas Hodges were paid for cutting stone. This work carried on for several months, though the account book is interspersed with expenses such as the cartage of thousands of bricks and tons of cement by Isaac Parfit; more timber delivered by Thomas Shannon (who normally carted wool at Anlaby during shearing); sundry goods received from Cossins & Brewster (storekeepers in Kapunda); rail freight to Gawler followed by carting to Kapunda, and much more.

Thomas Costello, who regularly transported wool for Anlaby, was engaged carting sand and lime for mortar, and two blacksmiths – Matthew Blackwell and Edward Moyle – forged a variety of metal wares to assist building work.

In December 1857, the expenses started to mount quickly: Robert Anderson was paid £400 for building 2000 yards of wall (presumably calculated by courses of stone), Nicholas Pascoe was paid £133 for quarrying 2000 yards of stone, and the Adelaide-based business, Simon C. Lohrmann & Son, was paid £127 for 35 weeks of carpentry work. The final account for the year was for Patrick Hartney, a carter, who had been engaged continuously since September at 18 shillings a week. The total expenditure for 1857 stood at £2146.

In February 1858, Richard Dooley, Henry Bruce, Frederick Sanders, and a Mr. Baker, were engaged in stonecutting. A Mr. Wilson was kept busy procuring sand, while Isaac Parfit transported 3 tons and 14 hundredweight of timber and glass to the house. Robert Anderson, the master mason, was kept busy from March to September building walls, with help from his assistants Auguste Gepperte and Michael Devitt. Thomas Thorpe and Bernarde Goode also received payment for carpentry work rendered. (It seems Thorpe and Goode were employed by English & Brown to undertake work at Anlaby.)

In July 1858, A. L. Elder of London was paid £40 for 210 yards of water pipe; local resident, James Hanlin, was engaged to cart it to Anlaby. Several tanks arrived in October, and John Foreman and Thomas Humphries were paid for sawing wood on site. A man called ‘Thomson’ was also paid for painting services, though his identity is obscure. The prominent Kapunda identity, Doctor Blood, was also paid for medical services rendered.

Across October and November, Samuel Potter was paid for 220 yards of flagging, while more cedar arrived on site, and English & Brown again supplied timber for the house. In December, Robert Dodgeson, a plumber by trade, was paid for installing pipework in the house. He continued to work into 1859.

As the year came to an end, several accounts were settled. On 31 December, Peter McLaren of Kapunda was paid £119 for plastering and slating the house. Nicholas Pascoe was paid £100 for quarrying 3112 yards of stone. Simon Lohrmann’s annual wage for carpentry was listed as £187 at year’s end.

In January 1859, Isaac Parfit carted 4.5 tons of timber to Anlaby, as well as 3 tons of cement, for which he received £9. Expenses started to peter out throughout 1859. There were relatively few accounts to pay: to Thomas Humphries for the sawing of wood; to English & Brown for cement; to Edward Jennings of Kapunda for log pine; to Simon C. Lohrmann & Son for locks; and Cossins & Brewster for sundry goods.

In July 1859, English & Brown were paid £18 for ‘preparing plans, drawings, specifications, agents, supplying tracings, and copies for res. at Anlaby.’ In addition, they were also paid £38 10s for ‘Mr. English expenses and time visiting and inspecting the building for the purpose of measurement. 7 journeys.’

Though the architect and builder had left the site – which indicates the house was virtually finished – Andrew Casanova was kept busy completing plumbing inside the house. Robert Anderson, the master mason, was also engaged to lay concrete to the tune of £4. A few months later, in October, Peter McLaren was engaged to lay cement at the front of the house, and Simon C. Lohrmann, the German-born carpenter, received final payment of £156 12s for 43 weeks of work.

The final entry relating to the House Account dates to 31 December 1859 and covered sundry goods. The total cost came to £5020 17s 1d, which equates to $984,000 in 2023. The entire house was paid for by Frederick Dutton: the expense is listed in his private account in the ledger book for 1859. After two years of construction, Alexander Buchanan finally had a residence to befit his status as manager of Anlaby.

The ‘House Account’, which continues over three successive ledgers, describes the construction of the house in fantastic detail. We know what supplies were ordered and often when they arrived, the rates of pay, the timing of construction, and even the names of the men who expended blood, sweat, and tears to make the building a reality.

The ledger books also confirm construction of the main homestead at Anlaby commenced earlier than first thought. While scaffolding was being erected in June 1857, construction had likely already commenced given that several rooms are located below ground level. Construction was virtually complete by July 1859, with the remaining work concentrating on plumbing, carpentry, and exterior cementing. To have built such a large home in two years – and one that is so far removed from the commercial networks of town life – is an extraordinary feat. On a broader level, Anlaby is now strongly linked to a number of heritage icons in South Australia, including Government House and Parliament House.

This significant discovery concerning the house’s construction may also come to redefine our understanding of the early development of the garden. Anlaby may gain further recognition in terms of botanical significance in the years to come.

Unearthing Anlaby’s genesis breathes life into the early history of the property, as well as the workers involved in creating a sturdy legacy of stone and mortar. Together they created a home for two dedicated managers, four generations of the Dutton family, and three succeeding families determined to keep the house alive and upright. While 2024 marks 185 years since the property’s foundation, the homestead at Anlaby has been a lived-in piece of history for 165 years and counting.