14 Apr 2023 ANLABY’S LOST CONSERVATORY

REDISCOVERING HENRY DUTTON’S MONUMENTAL GARDENING OBSESSION

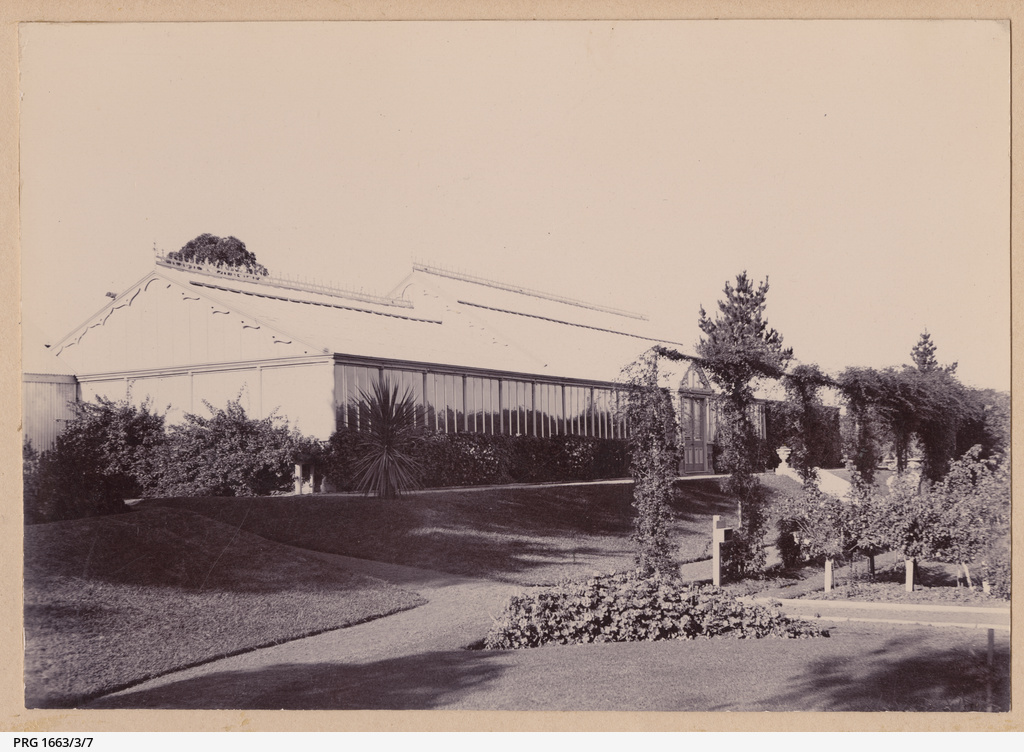

On the north side of the Anlaby homestead sits a series of low walls, partly covered in ivy, and overgrown with creeping fig and succulents. The walls are dotted with ornate circular vents and the floors are covered in imported encaustic tiles. The walls once formed the base of a grand, enormous conservatory built in the 1890s by A. Simpson & Son of Adelaide. As memories of the structure faded following its demise, its true origin became an enigma. In the coming months, stone masons will come to Anlaby to begin restoring the walls. In light of this, what can new research tell us about the genesis of this majestic house of glass and iron?

In mid-1890, Henry Dutton inherited Anlaby from his uncle, Frederick, who died at the Buckingham Palace Hotel, London. Henry’s circumstances changed dramatically: he resigned from his day job as a bank manager in Mt Pleasant to assume the role at the head of a vast pastoral estate.

Following the resolution of legacies, trusts and assets relating to Frederick’s will, Henry set about improving Anlaby by landscaping the gardens, constructing a new manager’s residence, and redesigning the main residence to befit his new status. He hired Frank Naish – the often-overlooked architect who designed Elder Hall on North Terrace – to assess the Anlaby homestead and design additions and alterations.

Adam Munro, a builder based at Kapunda, was contracted to make the many improvements a reality. From January 1891, his work consisted of building a fowl house as well as a lean-to at the back of the house kitchen, reinforcing creepers in the garden, digging a duck pond, installing marble steps, laying pipes and tiles, constructing a hay shed, erecting tank stands, repairing the stables, painting, cementing, and other sundry work. The improvements cost Henry £2,225 in 1891, or around $400,000 in 2022. The air hummed with activity.

In 1891, Henry committed to building a grand conservatory on the north side of the house. It is likely early design conversations with A. Simpson & Son, an Adelaide based firm, started within the first few months of the year. Founded in 1852, A. Simpson & Son was the largest metal manufactory in Australia by 1890. They fabricated tinware, ironware, and enamelware products, including safes, gates, ovens, saucepans and other general wares. The variety of goods fabricated by the men on site allowed the firm to accept creative, ambitious projects, such as Henry’s grand conservatory.

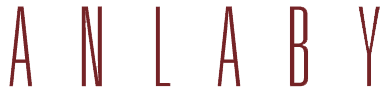

A. Simpson & Son collected hundreds of catalogues from around the world, probably to keep abreast of competitors and adapt to changing tastes and designs. In the company’s archives at the State Library of South Australia, the catalogue collection features manufacturers of everything from agricultural implements and door locks to surgical implements and stoves. Only two in the collection relate to conservatories – one from Henry Hope of Birmingham, who manufactured horticultural buildings for Queen Victoria among others, and Messenger & Company of Loughborough. On the front page of each is inscribed the date of receipt by A. Simpson & Son: August 1891. It seems conceivable that Henry Dutton either viewed these catalogues directly to inform the design of his conservatory, or they were ordered by A. Simpson & Son to understand up-to-date conservatory design and the components required to fabricate a conservatory before proceeding further. Between August and October 1891, A. Simpson & Son manufactured the components for the conservatory – everything from iron muntins and brackets to pipes and ridge cresting – at their manufactory on the corner of Grenfell Street and Gawler Place

Both Messenger & Company of Loughborough and Henry Hope of Birmingham constructed lean-to, three-quarter span, and full span conservatories. Henry Dutton’s conservatory was full span, in other words, it was independent from any other structure, and the walls were of the same height on all sides. Conservatories of this type are ideal for vineries, especially since they allow maximum sunlight, though they require more pipe to heat, and the cooling surface is greater. Several conservatory designs advertised by the two firms are strikingly similar to Henry’s conservatory, likewise, the ridge cresting, pipework layout, and vent systems are close to the finished building constructed by A. Simpson & Son. Observe some details below:

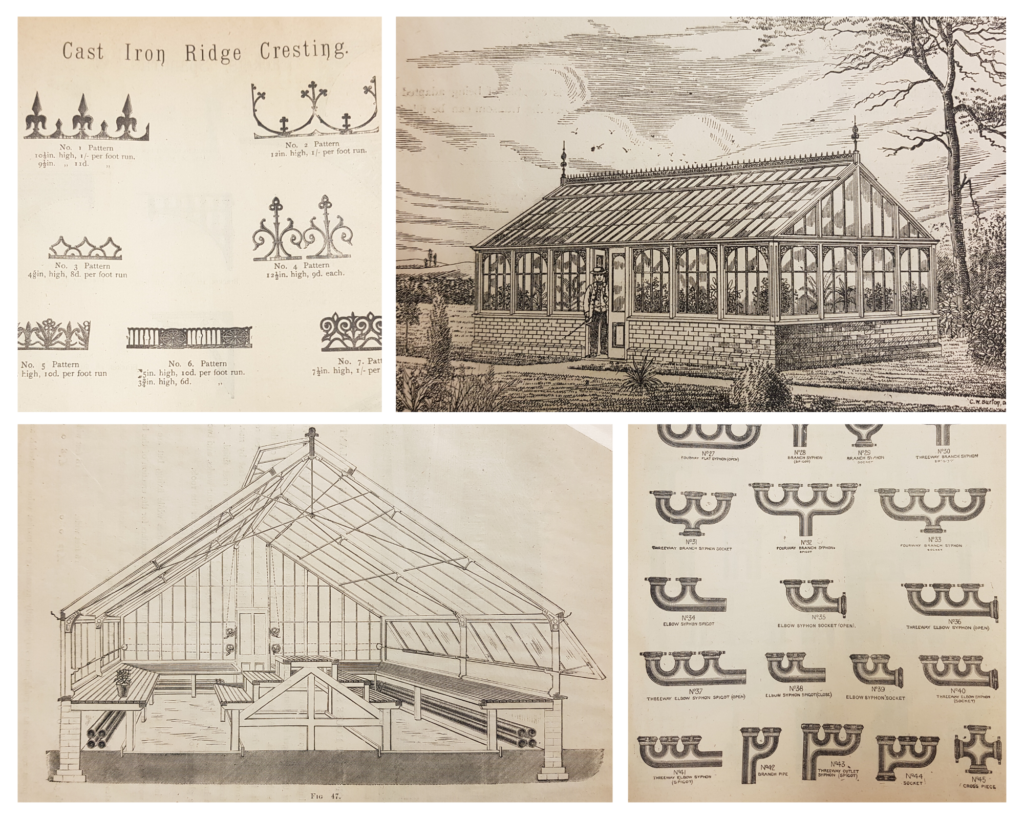

Before any work on the conservatory commenced, Henry ordered tiles for the interior floors in August 1891. The tiles were made by the internationally renowned firm, Maw & Company, based in Shropshire, England. A receipt from the Adelaide-based importing firm, T. Pritchard, reveals the exact order: 800 grey octagons, 800 fawn octagons, 1546 chocolate squares, 30 chocolate half dots, and 132 chocolate half 70s. Miraculously, the tiles from this order survive inside the conservatory today.

Work on building the conservatory commenced in October 1891, and was finished by mid-December. Adam Munro was hired to erect the stone walls, as well as the glass, iron, and wood structure on top. He was paid on 12 December 1891; the work being described as ‘To erecting conservatory.’ The cost came to £805, which equates to $150,000 in 2022. The sum Henry paid for the conservatory was between five and fifteen times the annual income of workers at Anlaby.

Despite Munro’s work, the conservatory was not yet in full operation. In March 1892, Henry received an iron tank, 5hp engine, and steam pump from H.B. Hawke and Co. in Kapunda, to heat the conservatory. In April 1892, Adam Munro was contracted to build an engine house on the western side of the conservatory to house the pump and engine. At the same time, he lay a concrete slab before the front door and erected decorative urns. In addition, he installed two tanks inside the conservatory and blinds on the roof of the structure to shield the sun.

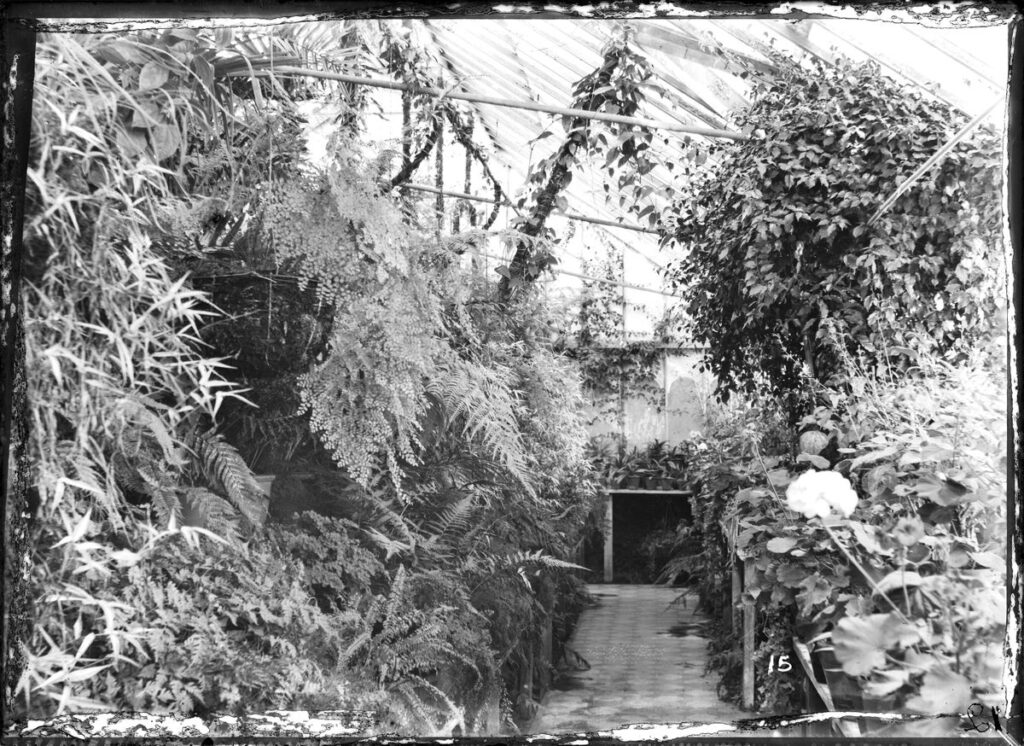

The finished conservatory was divided into thirds, with varying climactic conditions in each third. On the western end the conditions were dry and temperate: there was no open water to raise the humidity. The boiler house was located just outside, and the pipes entered the building in the western third. In the central third, a large pool was dug into the earth, lined with concrete, and filled with water. As the water warmed, it vaporised, creating a warm and humid environment ideal for growing orchids and more. A strong rack system was constructed above the pool, supported by metal supports stretching from one side of the pool to the other, to accommodate a variety of plants.

In the eastern third, a grotto was established: internal rockwork was planted with ferns, palms, and creepers. These mingled between small ponds and waterways, creating a lush, moist environment. In this section, however, the walls and ceiling were constructed of slatted hardwood, not glass and iron. The appearance was not dissimilar to gratings in a shearing shed. The design was intentional: the slatted hardwoods allowed sufficient shade and sunlight, and provided good rainfall, temperature, and humidity control.

Photographs of the central section of the conservatory reveal a diverse variety of plants were once grown there. Multiple varieties of ferns, African violets, bromeliads, pepper vine, dendrobium orchids, geraniums, bamboo and much more. An even greater variety of plants is visible in photographs of the grotto: aspidistra, parlour palm, aucuba, flax lily, monstera, philodendron, stag horn, tillandsia or air plants, Spanish moss, morning glory, cast-iron plant, and varieties of ferns, including asparagus fern, New Zealand fern, tree fern, and ostrich fern. This list barely scratches the surface.

The approach to the conservatory was amended several times over the course of its existence. In its first iteration, a wooden latticework walkway, with a steep roof, was installed. In the left picture below, Henry Dutton can be seen sitting on the ground, with his son, Harry, standing at the entrance of the conservatory accessway. This was later changed: a series of solid metal posts linked with hefty chain, were erected. The final iteration, erected around 1910, consisted of four archways constructed of galvanised irrigation pipe. Pillar roses were trained up and over these archways, creating tight bands of scent and colour.

The gardens at Anlaby were regularly opened to the public for fairs. Food, drink, and amusements were available for entertainment, as well as the opportunity to wander through the gardens Henry established. Visitors often marvelled at the conservatory, as well as the other structures in the garden, and heaped praise on the gardens, proclaiming them to be the best in South Australia.

The conservatory stood until the early 1960s, at which point Emily Dutton, the wife of Harry Dutton (a third-generation Dutton), lived in the house and managed the estate. Local stories maintain that in the early 1960s, local children were encouraged to smash the glass in the conservatory, supposedly being paid for each broken pane. Insurance issues seem to have played a role in its demise, and the schoolkids were used as easy scapegoats to hasten the structure’s end. After the glass was broken, the iron skeleton would have been torn down and presumably sold for scrap. No section of the ironwork survives today – even the pipework was dismantled.

Charlotte Calder, a granddaughter of Emily Dutton, recently visited Anlaby along with other members of the Dutton family. When asked of her memories of the conservatory, she vividly remembered the central third of the conservatory full of lush, green, growth. Likewise, the grotto section of the conservatory was in good condition. The western third of the conservatory was closed off, however the building was seemingly in good shape. The cost of maintenance may have been simply too much, especially since the estate was no longer as profitable as it once was.

Thankfully, the conservatory’s stone walls were left in situ, taking on a new existence as fanciful ruins in the garden. In 1964, the pool in the central section was heightened to be used as a swimming pool. Geoffrey Dutton, the last generation of the Dutton family to own the house, was a noted author, historian, and lecturer. Among his social circle of artists, poets, authors, and musicians was Belgian-born naïve painter, Henri Bastin. One day in the mid-1960s, he arrived unannounced at Anlaby to paint the floor of the swimming pool in the former conservatory. Unfortunately, no photos have come to light capturing his work and his work no longer survives, as he used paints unsuited for use in a swimming pool.

Since 1978, when Anlaby was sold by the Dutton family, the conservatory has lain overgrown and dormant in the upper garden. This, however, is about to change. Recently, Anlaby received a grant to assist with several improvements on site, one of them being the gradual restoration of the conservatory’s stone walls. (More on this grant soon). In the coming months, stone masons will commence work to restore the walls, protecting them for the future. The eventual plan is to restore Henry’s monumental conservatory, resurrecting his grand gardening vision, though this will take time. Until that day when Henry’s vision is once again restored, we can only peer at black and white photographs in awe.