08 Sep 2023 Clip, clip of the shears: Anlaby’s magnificent Woolshed

Over the hill from the main homestead sits the Anlaby Woolshed. Imposing and sturdy, millions of fleeces of wool have been shorn inside over the last 150 years. What is its story?

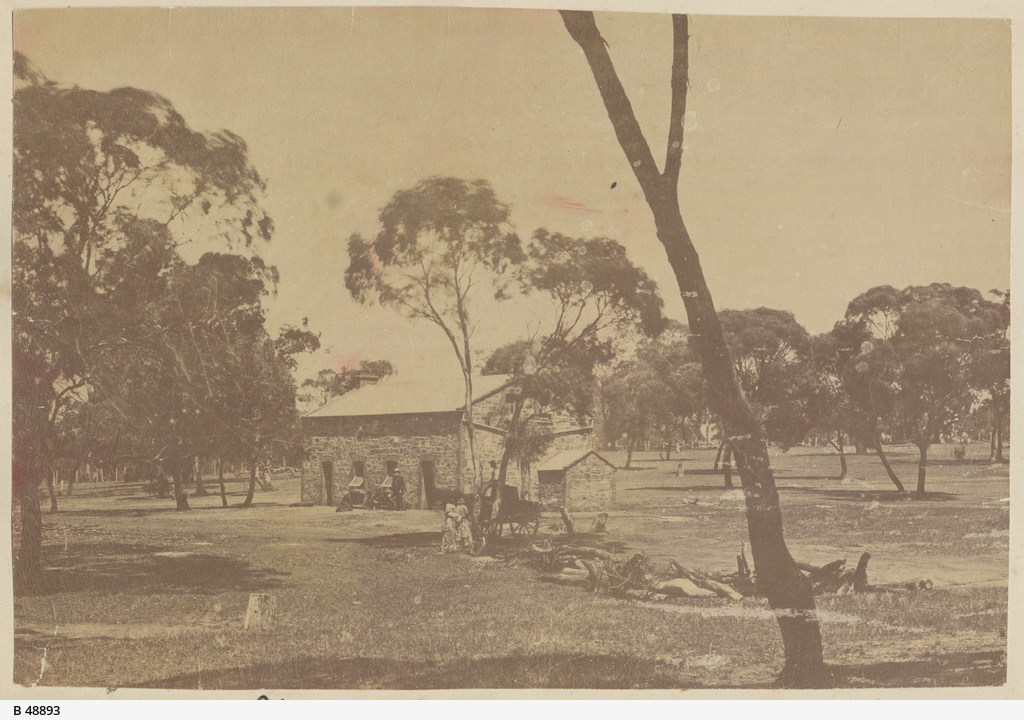

The first woolshed at Anlaby would have been constructed around the early 1840s. From later descriptions we know it was a wooden-slab structure, possibly with a shingle roof, and would have been one of the earliest structures built at Anlaby, after all, shearing sheep was integral to the financial wellbeing of the property. Like Bungaree Station near Clare, the woolshed came before all else – stone-built cottages, a manager’s residence, or stables – so important was the production of wool.

An account from 1869 captures shearing time in detail: “Time, 6 a.m. The pens full of sheep. Fifty men standing in front of the pens, each eagerly scanning the various animals before them with a view of seizing at the given time the particular sheep which he deems most suited to his purpose. At the first stroke of the 6 o’clock bell there is a simultaneous dart into the flock, a grab at the hind legs, a light scuffle, and in less than a minute nothing is heard save the clip, clip of the shears.”

The correspondent goes on: “As the fleeces fall they are picked up by boys, who throw them on the tables, where they are rolled up by sable Venuses [i.e. women] and carried to the sorter, who divides them into two sorts, viz. – the best for combing, and the other for clothing. The fleeces then pass into the hands of the pressmen, of whom there are nine. They manage three presses – two ordinary presses worked by the screw, which forces the wool together in the bale in such a manner as to enable the top to be sewn on; from these the bales are placed in the hydraulic machine, which squeezes them tight, and in this the iron hoops are fastened by an iron stud, which is a great improvement on the old plan of rivetting [sic]. Having been rolled out, weighed, and branded, they are loaded and sent to Kapunda, to travel by train to Port Adelaide for shipment.”

After thirty years of use, the time came for the erection of a new woolshed to keep pace with technological advancements and match the flourishing state of the property. In May 1871, advertisements started to appear in newspapers across South Australia calling for tenders to build a stone woolshed at Anlaby. Architectural plans were drawn up and the manager of Anlaby, Henry Morris, placed them at the Sir John Franklin Hotel, Kapunda, for perusal.

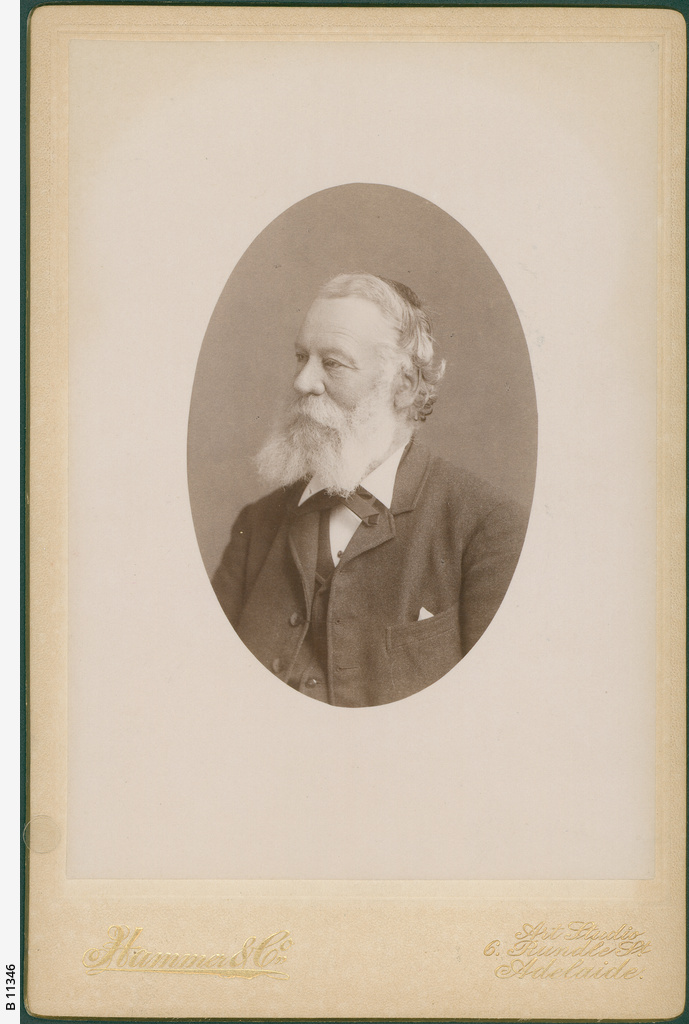

The woolshed at Anlaby was designed by the prolific architect, William Gore. Gore arrived in South Australia in the 1850s and spent much of his early career in the state’s south-east, where his architectural talent included a broad variety of structures. He designed impressive homesteads and two-storied hotels, warehouses and general stores, banking chambers and riding stables, schoolhouses and soaring churches, and, of course, woolsheds. Some of the woolsheds he designed include Glencoe, Katnook, Wrattenbullie, and Glenroy (now Bellwether Wines). His impressive array of work can still be found in Penola, Naracoorte, Mount Gambier, and elsewhere across the south-east.

On 8 May 1871, Gore was paid £20 ($3,725 in 2023) for his services. Just over two months later, on 11 July 1871, construction started. Henry Morris placed £1 on the foundation stone to mark the occasion. The task of building the woolshed fell to Johann Friedrich Schramm of Kapunda. Schramm was a German-born immigrant who travelled to South Australia in 1850. He worked as a storekeeper in Kapunda – selling everything from German wine and Cuban cigars to chaff and cornflour – and served as a local councillor. He later turned to selling building materials, including timber, galvanised iron, and ironmongery. Exactly how Schramm won the tender is unclear, for it seems he had no direct experience with masonry.

Concurrent with the construction of the woolshed, the Shearer’s Kitchen was built a short distance away. This building, it seems, was not architect-designed, though Henry Morris still placed 10 shillings on the foundation stone. Peter Mclaren, a plasterer and contractor at Kapunda, won the tender to construct the building and on 14 October 1871, he was paid £307 ($57,000 in 2023) for services rendered. Basic accommodation was fitted out in the large room upstairs, while on the ground floor, hefty ovens, furnaces, and boilers were installed in the kitchen to cook food for the hungry shearers. They would be sorely needed: in 1871, the shearers consumed copious amounts of bread, the carcases of eight to nine sheep, and between 60 and 70 gallons (272-318 litres) of tea per day! It was like feeding a small army every day!

Despite this, construction was rapid, for the shed had to be completed in readiness for shearing, which was due to commence on 15 September 1871. Schramm and his workers were busy erecting structural beams, constructing stone walls, installing heavy wool presses, fitting out battened floors and wooden gates, and pointing stonework with lampblack (a type of soot used as a pigment). This work was overseen by a prominent civil engineering firm, English & Rees, who inspected the building four times to ensure its structural stability. Thomas English and Rowland Rees were civil engineers and architects based on Currie Street, Adelaide. Following these inspections, Schramm was paid on 6 October, the total coming to £817 12s 7d (equivalent to $152,000 in 2023).

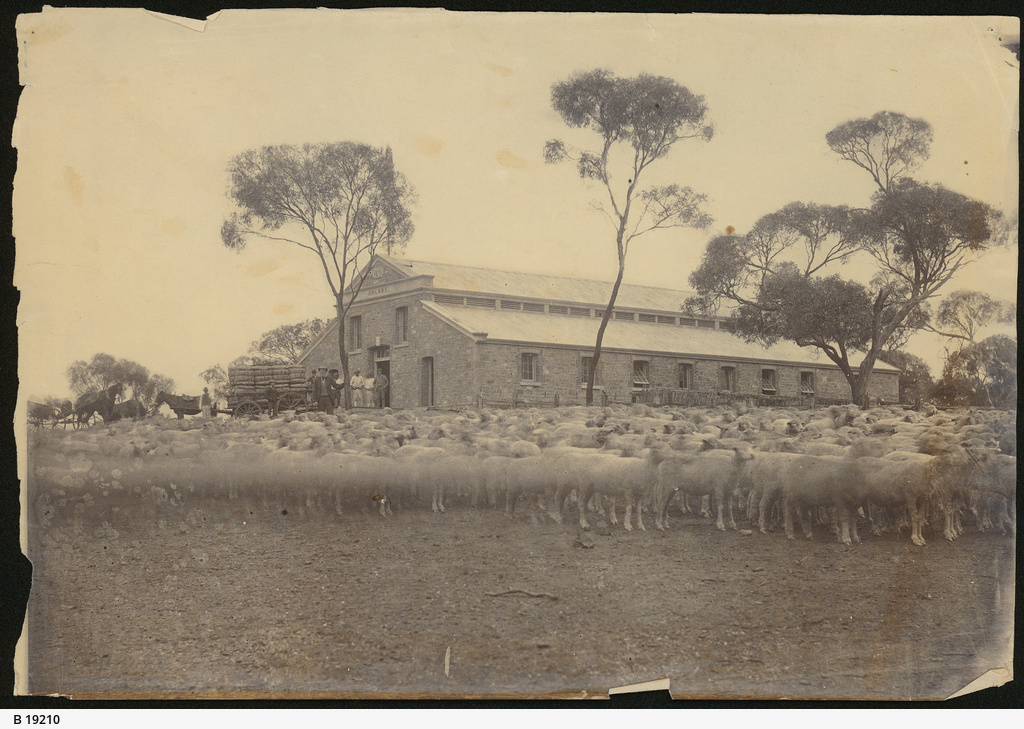

An article from the Adelaide Observer of 28 October 1871 mentioned “the new woolshed is admirably situated on a hill, and shows to advantage from every side.” The correspondent also described the shed, which measured 85ft. by 46ft, as having a holding capacity of 500 sheep, and that 3000 sheep could be shorn in the shed every day. “All the arrangements show great forethought,” the correspondent commented later.

Now that the new shed was up and running, the old woolshed was demolished. It was, in fact, sold off for materials, all except for the battened floor. Presumably, this was put to use in the new woolshed.

Since construction, Anlaby’s woolshed has echoed with the click of handheld shears, the straining of wool presses, the curses muttered at misbehaved sheep, and the gentle rustle of fleeces passed from one pair of hands to the next.

In 1871, shearing commenced on 15 September. Throughout the next eight weeks, 40 shearers worked in the woolshed shearing around 52,000 sheep, though the average number of shearers working at any time was about 30. The average number of sheep shorn per individual was about 1285, but a few soared above the pack. One shearer, called Edward Hams, managed 2,779 during the season, and Ernst Blesing wasn’t far behind him at 2,717. At the other end of the scale, August Mader only managed 16 sheep, which leads one to believe he was merely having a go at the blades for an afternoon.

Shearing time was a prime opportunity for farmers and farmer’s sons from near and far to come together and earn good money before the rush of the grain harvest season. Some shearers went from woolshed to woolshed throughout the season, starting on the northern pastoral runs before working their way south. At Anlaby, shearers were paid 15 shillings per hundred sheep shorn (roughly $140 in 2023), which provided a great opportunity to earn money quickly. For example, one shepherd at Anlaby, William Hams, earned £35 per annum, but for the shearing season he picked up the blades and shore 1,924 sheep, earning £14 – or around 40% of his annual income – in eight weeks.

In addition to the shearers cutting the fleece, there were roustabouts, boys who picked up fleeces, wool classers, wool winders (who packed the fleece into the bales), pressers, and waggoners. Waggoners took the bales directly from the woolshed to the nearest railway station, or in the earlier years, directly to port. As soon as a load was full, it from the loading bay at the front of the woolshed. Normally around 1500 bales could be produced in a single season – even in 1904, when the flock had been reduced to 41,000, 1043 bales were sold on the market. Altogether, the number of workers involved in the annual shearing season hovered around 70.

First Nation workers – called ‘Blackfellow’ or ‘Blackwoman’ in wage books, as per the language of the time – also took part in various jobs at shearing time. They were involved in rounding sheep up, sorting wool, and shearing sheep. (We hope to feature more of Anlaby’s First Nations history as we learn more about this important chapter.)

In 1904, it became necessary to extend the shed. Adam Munro, a local contractor based at Kapunda, was commissioned to erect a galvanised iron extension, following the same form as the original, for undercover yards at the rear of the shed. Munro also modified the front of the shed by reinforcing the loading bay and adding decorative fascia boards. The woolshed witnessed the introduction of new technologies, from stationary engines and driving wheels to the Koerstz wool press, which is still operational to this day. Koerstz wool presses transformed the efficiency of packing and transporting wool, following its invention in the 1890s. Instead of employing several men to press the bales, it could be operated by one man, not to mention it squeezed more fleeces into a single bale and occupied less floorspace.

Despite changing practices, Anlaby’s woolshed also bore witness to the gradual decline of the estate as tranches of land were sold to pay for property elsewhere, lavish holidays, or house extensions. By the late 1950s, the Merino flock numbered less than 10,000. The woolshed served the Dutton family for almost a century.

During a land auction held at Anlaby on 18 April 1968, two graziers from Robertstown, Frank and Donald Mosey, purchased the woolshed and surrounding property. Two generations of the Mosey family operated a sheep breeding enterprise both at Anlaby and east of Burra on a property called Euravale. Though the woolshed was still used for its original purpose, it was disconnected from the main homestead to the south.

The woolshed became part of the main property again in 2009, when Andrew Morphett and Peter Hayward, the present owners, purchased the shed and surrounding property. More than 150 years after it was built, Anlaby’s Woolshed continues to hum with activity – from bleating sheep and whirring handpieces to the heave of hydraulic presses and the slurping of coffee at morning smoko.