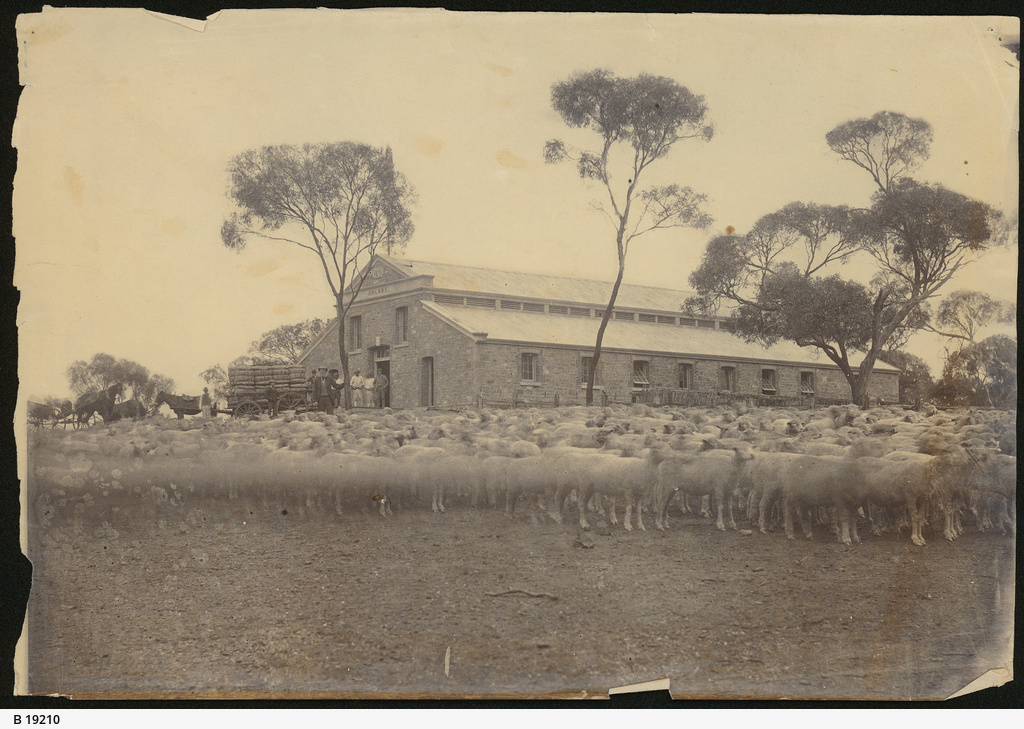

16 May 2025 The Great Overland Gamble: How Anlaby Began

In South Australia’s early years, the colony’s hunger for opportunity was matched by a pressing need for food. With livestock in short supply, ambitious pastoralists looked to the untamed lands between Sydney and Adelaide. Among them were Frederick and William Dutton, who, with commercial partner Captain John Finnis, financed one of the era’s boldest overlanding ventures. This article follows the remarkable 1839 expedition, led by Alexander Buchanan, who helped drive thousands of sheep across a harsh and unpredictable landscape. From treacherous river crossings to relentless drought, Buchanan’s journey captures the risk and resilience behind Anlaby’s uncertain beginnings—what started as a daring commercial gamble would quietly establish one of Australia’s most enduring sheep stations.

![Figure 1: Frederick Hansborough Dutton. Source: SLSA [B 14653].](https://anlabyaustralia.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Figure-1-Frederick-Hansborough-Dutton.jpeg)

Frederick Hansborough Dutton was born in April 1812 in Colne, Lancashire, a market town known for its woollen industry and canal links. His father, Frederick Hugh Hampden Dutton, a shopkeeper, became British Vice-Consul at Ritzebüttel near Hamburg in 1816, prompting the family’s move to Germany. There, young Frederick likely learned German, as did his brothers Francis and William. William even studied at the German Agricultural Academy in Möglin, founded by leading agronomist Albrecht Thaer. Thaer’s progressive ideas on Merino sheep—focusing on skin quality, nutrition, and genetic traits—would later influence the Duttons’ pastoral success in Australia.

Frederick’s education remains unclear but likely took place in Switzerland and Germany, possibly including Möglin. At 17, he sailed to Sydney aboard the Lady Blackwood in March 1830 to join William. Over the next nine years, the brothers developed pastoral runs across New South Wales, including the Yass Plains, Mullengendra, and Monaro. In 1837, they overlanded 560 cattle to Portland Bay—a major feat. William, the elder, likely mentored Frederick using his Australian Agricultural Company experience. In 1839, he purchased a 4,000-acre Special Survey in the Adelaide Hills and shipped 19 rams from Sydney to Adelaide, selling them for £200—marking the start of the Duttons’ move to South Australia.

This foundational experience in livestock husbandry and pastoral enterprise laid the groundwork for Frederick’s eventual move to South Australia and the founding of Anlaby Station.

Established in 1836, one of the first tasks in the new colony of South Australia was to secure food supplies. Large numbers of livestock were needed to kick-start agricultural production. Sensing a commercial opportunity arising from the threat of famine in Adelaide, John Hawdon and Charles Bonney became the first to overland livestock from interstate when they drove 300 cattle from Goulburn to Adelaide, arriving there on 3 April 1838. Their pioneering journey filled the bellies of meat-starved Adelaidians and proved that walking cattle overland could be done.

![Figure 2: L-R: Joseph Hawdon and Charles Bonney. Source: SLSA [B 7389] and [B 7390] respectively](https://anlabyaustralia.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Figure-2-L-R-Joseph-Hawdon-and-Charles-Bonney-1024x577.png)

Overlanding sheep, however, remained a live issue in 1838, especially the concern about the sheep’s condition on arrival. Convinced of its practicability, famed explorer Edward John Eyre overlanded 1000 sheep from NSW, becoming the first to do so. He arrived in Adelaide in March 1839, and proudly announced that stock losses on the route did not exceed 1%. To ease doubts about the condition of the sheep upon their arrival, Eyre gifted a freshly slaughtered saddle of mutton to Governor George Gawler, who replied the meat “could not be surpassed in appearance by any in a London butcher’s shop at Christmas.” In July 1839, the second importation of sheep, commandeered by the younger brother of Charles Sturt, brought a further 5,000 sheep to the colony. This second overland trek assuaged the concerns of many and catalysed a steady stream of livestock from Victoria and New South Wales. The stakes were high, and the game was on. Who would risk it all to drive their flocks across unfamiliar country? Who would face the wilderness to claim a fortune in South Australia?

Into this heady atmosphere of fortune-chasing stepped Alexander Buchanan. Born in Glasgow as the son of a coffee plantation owner, Buchanan was educated in Scotland before gaining mercantile experience in England and Canada. In 1838, after returning to Scotland from Canada, he determined to sail for Adelaide aboard the Welcome, which arrived on 3 April 1839.

Two months later, on 3 June 1839, Alexander Buchanan boarded the Resource bound for Sydney. He was part of a company of seven other young men who sought to find work by walking sheep from New South Wales to South Australia as a speculative gamble. During the voyage to Sydney, Buchanan travelled steerage for the first time to save money, about which he wrote in his diary, “I shall never do so again.”

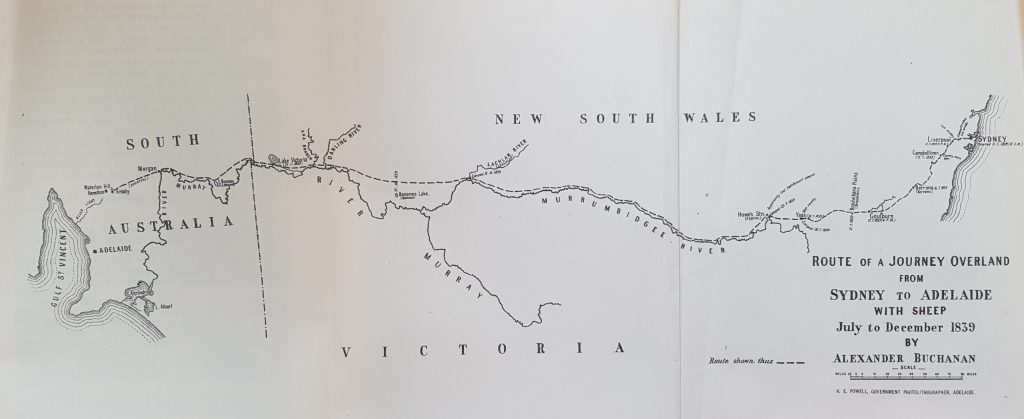

The group arrived in Sydney on 17 June 1839. In the following weeks, Buchanan met with Frederick Dutton to confirm arrangements for the overland expedition, including provisions and where to collect livestock. According to Buchanan’s diary, the party departed Sydney on 11 July 1839. They reached Liverpool the following day – which Buchanan described as a “very nice little village” – and Campbelltown on 13 July. Berrima was reached on 16 July, Goulburn on 19 July, and Yass on 26 July.

![Figure 3: Alexander Buchanan, c. 1860. Source: SLSA [B 1851] .](https://anlabyaustralia.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Figure-3-Alexander-Buchanan.jpeg)

On 29 July, they arrived at Mr. Howe’s station to the west of Yass. This is where Buchanan and his team of men, consisting of 2 bullock drivers, 1 carter, 1 cook, 4 shepherds, and 4 others, collected 4,000 sheep purchased by William and Frederick Dutton, along with their commercial partner and relation, Captain John Finnis. Buchanan’s party had to check the sheep for disease, draught the sheep to check for sex and age, and feed and rest the horses for the onward journey. Buchanan only left Mr. Howe’s station on 17 August, explaining they “spent the time we were staying at Howe’s principally shooting ducks and watermoles (platypuses)…”

On 18 August, the sheep were walked in three droves to ensure efficient feeding and travel. Just two days later, they encountered a mob of sheep belonging to Captain King whose 200 wethers accidentally mixed with the flock. The entire flock under Buchanan’s charge had to be redraughted and counted, leading to a delay of two days, which was made all the more difficult by needing to move the draughting away from a grogshop which Buchanan feared would intoxicate the shepherds and stockmen.

On 23 August, Buchanan and several men travelled to a Mr. Stuckie’s station, based near Gundagai, to collect 900 sheep that Dutton and Finnis had purchased for the overland trek. It was a trial to walk them to the main flock. Though the specific waterway is not mentioned, Buchanan describes having to cross the 900 sheep over water on a small square punt about 2.5m by 1.5m in size and held 25 sheep at once. The waterway was likely an offshoot of the Murrumbidgee, which they regularly followed west after Yass. Crossing rivers was a tough task: after crossing these 900 sheep, they pulled out a bogged dray and in doing so one of the mares drowned. “So much for profit and loss,” wrote Alexander Buchanan.

During late August and into September, it was not unusual for the nearly 5500-strong flock to only walk between 4.8km and 6.5km a day as many of the ewes were in lamb. Many of the observations in Buchanan’s diary relate to the quality of feed for the sheep, buying provisions for the men, and walking in tandem with the supply drays. Writing on 21 September, Buchanan expressed relief at having enough provisions for 12 men for 12 weeks until arrival in Adelaide. On the same day, Buchanan wrote “the rest of our party have remained behind to bring on the other two flocks – in all about 13,000 more.” The origin of these sheep is unknown, but it becomes clear that the entire flock being walked was 18-18,500 sheep, and that Buchanan was part of a much larger operation.

While trekking west, Buchanan intersperses his diary with a number of intriguing reflections. On 30 September he describes the excitement of chasing emus. “They ran like the very wind,” he complained, which made it hard to keep up, but one of his fellow stockmen, Mr. Cunningham, somehow managed to avoid injury while doing a complete somersault on the horse! Buchanan refers to dry conditions on the northern side of the Murrumbidgee, describing the area around the Hay Plains, NSW, as “parched up with drought.” He refers to First Nations people on several occasions, including seeing them on the riverbanks, coming upon huts with fires burning, and waving green boughs. There were times when members of Buchanan’s team wanted to “break them” but he firmly decided the best policy was to “let abe for let abe” (‘abe’ is a Scottish word meaning ‘leave undisturbed’ or ‘let be’).

The sheep crossed the Lachlan River near Oxley on 16 October, before deviating northward. Buchanan missed the meeting of the Murrumbidgee and Murray rivers near Balranald, instead joining the Murray near its intersection with the Darling River at Wentworth in early November. The crossing of the Darling was complicated by a rogue heifer scattering the flock. The animal was slaughtered, which pleased Buchanan as it saved killing up to 8 sheep for rations. While crossing the Darling in specially constructed punts, the party of men encountered a Mr. Tooth with a herd of 550 cattle bound for Adelaide; this only highlighted the rush of overland expeditions itching to reach Adelaide. It was also while floating provisions across the Darling that one of the most tragic events of the expedition took place: a group of First Nations people, likely members of the Barkindji people, attacked Buchanan’s men, which he attributed to their desire for supplies. The men’s muskets killed 6 Barkindji people, and once the rest of them fled, their canoes and nets were destroyed. Encounters like were sadly all too common during overland expeditions, and it would not be the last musket fired in anger during this trek.

The sheep continued west, averaging between 8km and 24km per day, which meant the sheep reached Lake Victoria on 23 November and Lake Bonney nearly a week later. Buchanan criticised the country around the two lakes as scrubby, sandy, and dusty and appearing “to be nothing but a desert.” By the first week of December the expedition would have been in the area of Waikerie and Morgan. The stockmen and shepherds kept the sheep close to the river, which afforded the opportunity to hunt ducks and kangaroos and water the sheep as summer set in.

On 9 December 1839, Buchanan departed from the main group to ride ahead to Adelaide to prepare for the flock’s arrival. On the way, he encountered a surveying team that had departed Adelaide only ten days prior. The surveyors explained Governor George Gawler and Captain Charles Sturt were sailing upriver from Lake Alexandrina. Buchanan changed course to meet them. He relayed information regarding conditions upstream, particularly the behaviour of First Nations people, and provided Governor Gawler and Captain Sturt with additional provisions.

On the way to Adelaide, Buchanan rode to a squatting station formerly occupied by Edward John Eyre. The site is described as being in the River Light Valley and is possibly where modern-day Anlaby sits. Alexander referred to the area as a “gentleman’s park [of] fine plains and thinly studded with trees.” He said it was exceedingly better than Kilkerran Park (a possible reference to Kilkerran House in Ayrshire, Scotland) and Eaton Hall, the residence of the Earl of Grosvenor.

From here the story becomes murky. Buchanan’s diary fails to mention the handover of sheep to representatives of Frederick and William Dutton and Captain John Finnis. It seems Captain Finnis was overlanding stock on a large scale at the time. A report in the South Australian Register from 5 October 1839, details the anticipated arrival of “Captain Finniss’s Overland Party,” and announced he had purchased an extra 4,000 sheep to be overlanded, bringing his entire overlanding gamble to 25,000 sheep and 7,000 cattle. This ‘Overland Party’ likely refers in part to the sheep under Buchanan’s care.

On 14 December, the same newspaper proudly announced the safe arrival of 6500 sheep into South Australia, which were part of the “extensive flocks now on their way hither, belonging to Mr. [William] Hampden Dutton and Captain Finnis.” This is very likely the flock that Buchanan walked across. The report goes on to detail that another flock of 8,000 had crossed the Darling and a third was further off, with the numbers coming to about 25,000.

On 28 December 1839, the South Australian Register advertised the importation of seven thousand more sheep belonging to Messrs. Finnis, Dutton & Co. The sheep, it is stated, arrived under the charge of Mr. Cameron who reported “a most successful trip and very few losses.” The report also details that six thousand more were expected in January 1840. This report corroborates our understanding of Anlaby’s founding that 18,000 sheep were walked overland under the chief charge of Buchanan: Buchanan walked 5,000, Cameron brought the second flock of 7,000, and 6,000 followed in January 1840, making 18,000. However, other estimates range between 16,000 and 25,000 sheep. Despite the uncertainty over exact numbers, the fact remains that the passage of thousands of sheep overland, with relatively few losses, was extraordinary.

With the sheep successfully driven overland—through the finances of William and Frederick Dutton, along with John Finnis – and now arrived in Adelaide, the next course of action was to bring them to market. Unfortunately, the realisation quickly dawned that the sheep had arrived in a glutted Adelaide market. The rush to overland livestock to South Australia had created an oversupply of sheep and cattle.

The next part of the story is harder to piece together. Newspapers from March 1840 feature ads for large sheep sales by Dutton and Finnis, the first on 7 March offering 12,000 sheep. follow-up ad describes them as recently shorn, disease-free, and from “the flocks of the most celebrated breeders in New South Wales.” Interested buyers were directed to John Finnis in North Adelaide or Frederick Dutton at Miss Bathgate’s boarding house on Rundle Street. Dutton may have just arrived in Adelaide – o ne brief notice places him with Finnis and selling cigars, tobacco, and brandy from the recently arrived aboard the Mary Ridgway.

In 27 March 1840, Adelaide auctioneers, V. & E. Solomon sold 4800 wethers and ewes for Dutton and Finnis. This success, however, was short lived. Advertisement offering thousands of sheep persisted until July 1840. By July, Frederick was still boarding at Miss Bathgate’s eager to sell sheep. In fact, several notices state “Mr Dutton, having business of importance requiring his attendance in Sydney, is anxious to dispose of the whole of his stock in one lot.” The lot consisted of 4750 ewes of various ages, 6000 wethers, 26 bullocks, and 14 mares, in addition to a block of land in Hindmarsh and a wool press.

It seems by 4 August 1840, after dozens of newspaper advertisements, Frederick’s patience could endure no longer. On this date, mention is first made of Mr Dutton’s station, from where 12 rams had recently been received in Adelaide for sale. Directly underneath is a ‘Wanted’ notice looking for six good shepherds to whom 15 shillings a week and rations would be supplied. The hiring of shepherds, brought about by desperation and a glutted Adelaide market, heralded the earliest beginnings of Anlaby Station.

What began as a bold commercial venture by Frederick and William Dutton and John Finnis became a defining moment in South Australia’s pastoral history. The overlanding of thousands of sheep across harsh and unfamiliar terrain was a feat of endurance, organisation, and frontier negotiation. Yet it was the collapse of market expectations in Adelaide that forced a lasting decision: to settle. In doing so, Frederick Dutton inaugurated a pastoral property that would shape South Australia’s rural identity. The founding of Anlaby was not just a response to market forces – it was the beginning of a new chapter in the South Australia’s agricultural and economic development.